♥ R O Y A L B A B Y ♥

Let’s start with a baby gift to celebrate, because crikey, IT’S A BOY! MUSICA!

Let’s start with a baby gift to celebrate, because crikey, IT’S A BOY! MUSICA!

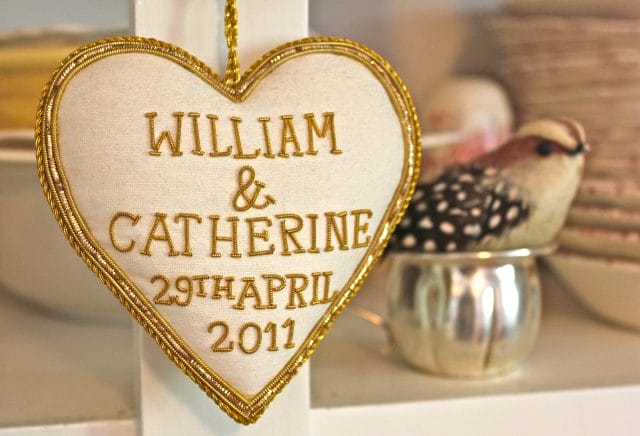

Must have something to mark this lovely event happening our own Mother country!

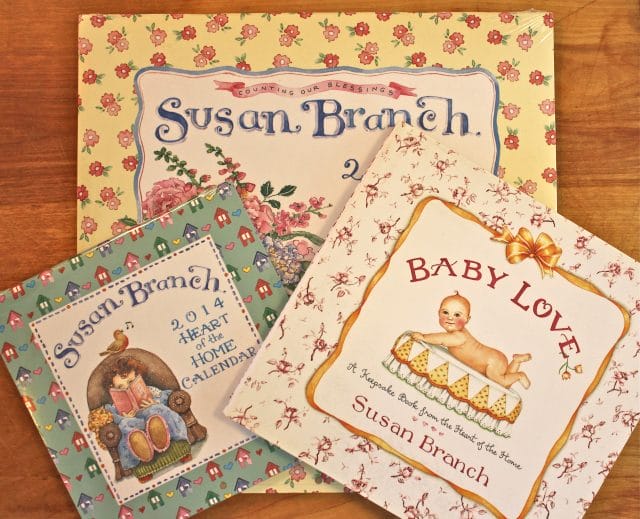

Something for a Royal Baby’s first year, my Baby Love book for new moms and dads to write about their own little royal baby, and two 2014 wall calendars to record his every adorable achievement. If you leave a comment at the bottom of this post, this signed set of goodies could be yours. Even if you aren’t welcoming a baby into your family right now, Baby Love is a jolly good thing for anyone’s “hope” chest.

Getting ready, washing cups . . .

It’s Sunday morning, the party is at 4:30 pm, we have no baby, but I’m happy because finally, the sun is just starting to come out.

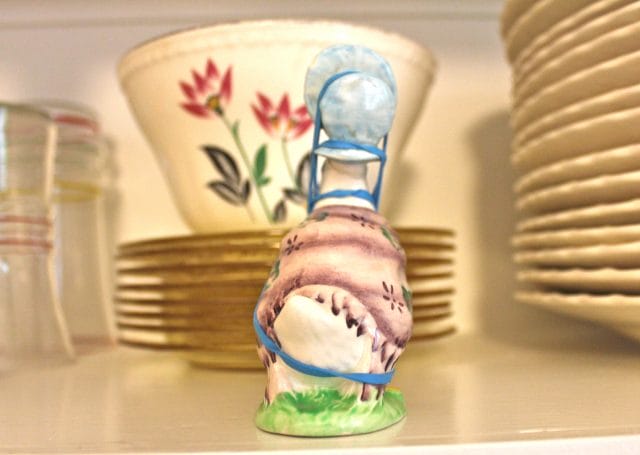

I’ve been lining the little shelf over the sink with flowers . . . squeezing them in amongst the Beatrix Potter People.

‘Course Jack is helping me . . . vaguely eyeing Jemima, thinking, “Don’t jump!”

‘Course Jack is helping me . . . vaguely eyeing Jemima, thinking, “Don’t jump!”

Joe hung up our new Downton Abbey bunting (white), and the flag we brought home from England; I plumped the “God Save the Queen” pillow my girlfriend Elizabeth brought back for me on one of her visits to England . . .

The Twine experts of all time came from California to help ~ that’s Diana on the left, and Elizabeth on the right. They have tea parties for their girlfriends every year, it’s a tradition they make new hats for each event. They are their own kind of royalty and their names (and the sunglasses) prove it. I loved having royalty at our party.

The Twine experts of all time came from California to help ~ that’s Diana on the left, and Elizabeth on the right. They have tea parties for their girlfriends every year, it’s a tradition they make new hats for each event. They are their own kind of royalty and their names (and the sunglasses) prove it. I loved having royalty at our party.

Other people see them as royalty too, here’s Paparazzi Cathy in her posh little ruffled gloves.

Here’s another photo of them and their hats! too cute! Just a tiny idea of how fun and creative a tea party can really be.

Diana and Elizabeth are cousins, their moms were sisters. They’ve known each other all their lives. You can see by the flags in the window that they love England too, and have also done the pilgrimage to Beatrix Potter’s house! I met Elizabeth when she bought my first house from me in 1989. The two of them left yesterday, but I had them here all week!

Making the perfect cucumber sandwiches was a snap for these two . . . along with egg salad sandwiches and smoked salmon with cream cheese on pumpernickel.

I baked an Orange Lavender Polenta cake . . . I’ll show you how to make it in the next post.

. . . I made cold slaw, carrot salad, stuffed eggs, watermelon balls with yogurt and brown sugar. We bought butter cookies from the Scottish Bakehouse, and Chilmark Chocolates too. Sixty guests, friends, neighbors, family, kids, and house guests.

Joe set up a bar, made a giant pitcher of Pimm’s Cup, with orange, lime and lemon slices and cucumber sticks . . .

Proof that it takes a village . . . More bunting drapes the arbor, there’s the cousins surveying the area . . .

It’s all just busy-work, because all we can think about is when is that baby going to be born! Someone runs to the TV every 15 minutes just to make sure nothing is still happening. And it always is.

We brought the Union Jack bunting home from England . . . I’ve been saving it for just this very day.

Of course we needed a talented person to play A Fine Romance and It’s a Long Way to Tipperary during the party … John Alaimo brought his piano.

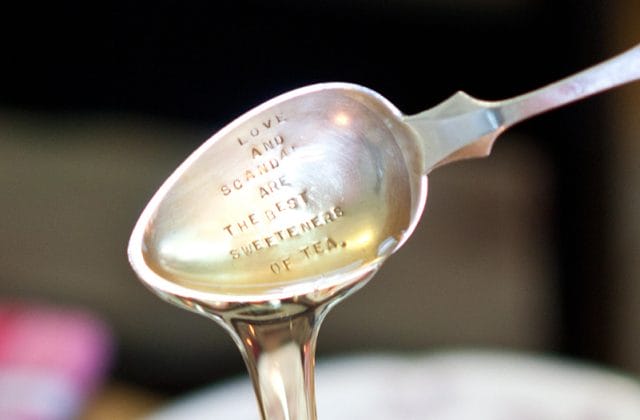

Getting it all together, teaspoons, sugar bowls, teapots and tea cozies . . .

We had little cloth covers for the creamers that keep any critters out of the cream!

I love the little details of tea . . .

Diana brought a cake topper she made for the Orange Lavender Polenta Cake ~ it looked darling. You could get one too, and see some of the other wonderful things in Diana’s Etsy store. While you’re at it, if you’d like to see what goes on in Elizabeth’s designing life, you can go to her website at Renovation-Design.com.

I forgot to take pictures of the food and tea table! This is the closest I got to the table with the camera. (Fear not, I got a lot closer without the camera!) The book about Diana (on the table) was a gift from our friend Linda . . . I’m sure Diana felt at home with all the other royalty ~ we loved having her here.♥ Just a little bittersweet without her. How she would have loved this moment.

I forgot to take pictures of the food and tea table! This is the closest I got to the table with the camera. (Fear not, I got a lot closer without the camera!) The book about Diana (on the table) was a gift from our friend Linda . . . I’m sure Diana felt at home with all the other royalty ~ we loved having her here.♥ Just a little bittersweet without her. How she would have loved this moment.

We know this baby is coming, it’s the talk of the town, but when, when, when?

We know this baby is coming, it’s the talk of the town, but when, when, when?

The Lady Olympia is going from person to person to ask “Will it be a boy or a girl?” What do you think the name will be?” Turns out the consensus is, it’s a GIRL, and her name will be Elizabeth! A few got a bit closer, saying it would be a boy, and they thought perhaps “Charles” or “William”. I like James for a boy because isn’t Jimmy just the cutest for a little Prince? King James would be nice for a king too. We’ll know pretty soon.

The Lady Olympia is going from person to person to ask “Will it be a boy or a girl?” What do you think the name will be?” Turns out the consensus is, it’s a GIRL, and her name will be Elizabeth! A few got a bit closer, saying it would be a boy, and they thought perhaps “Charles” or “William”. I like James for a boy because isn’t Jimmy just the cutest for a little Prince? King James would be nice for a king too. We’ll know pretty soon.

Lady Olympia takes a time out for hugs with her dapper white-linen and boater-clad Dad, the Duke of Earl, and her big sister, Crown Princess Astoria.

The Duke’s braces were brilliant!

Princess Marjorie, Grand Duchess Robin, Lady Diana, Countess Jill, and Queen Elizabeth. ♥

Queen Elizabeth tells a funny story!

Queen Elizabeth tells a funny story!

Princess Irenie lives in London and came to visit Princess Samantha who just graduated from St. Andrews in Scotland. I’ve known Princess Samantha since she was a little baby. When she was two and in her mother’s arms, she leaned toward me touching my earlobes, and said in pure baby talk, “I lob youa eahwings.” Cutest little thing in the world!

Because they are five hours ahead of us here on the East Coast, by this time it was dark in England and looked like this, and the brightest light was London. I think Princess Catherine was probably feeling a little bit queasy by now, probably walking around the living room, or cleaning out the kitchen cupboards. But we didn’t know that for sure. We thought she might need some help to get this baby going.

So just before the party was over, as twilight set in, we made a big circle and held hands. We said a prayer for Catherine, for  William, and for the baby. We prayed that the birth would be easy for everyone, the baby would be healthy and most of all, that it would come soon. Then we raised our eyes to heaven, lifted our hands into the air, and all together, we dropped our hands and said, Pushhhhhhh, and again, still holding hands, arms up and then down (like we were the white flag at a Nascar race), Pusssshhhhhh, and one more time: up, down, pushhhhhh. Like a mantra and a prayer. And guess what? Must have been moments later, the royal couple checked into the hospital! Well, I guess SO! And THAT is how we got the baby born.

William, and for the baby. We prayed that the birth would be easy for everyone, the baby would be healthy and most of all, that it would come soon. Then we raised our eyes to heaven, lifted our hands into the air, and all together, we dropped our hands and said, Pushhhhhhh, and again, still holding hands, arms up and then down (like we were the white flag at a Nascar race), Pusssshhhhhh, and one more time: up, down, pushhhhhh. Like a mantra and a prayer. And guess what? Must have been moments later, the royal couple checked into the hospital! Well, I guess SO! And THAT is how we got the baby born.

Oh, just now as I’m writing, the new parents with the new Prince just came out the hospital doors. So exciting! It seems to have gone swimmingly and all our prayers were

Oh, just now as I’m writing, the new parents with the new Prince just came out the hospital doors. So exciting! It seems to have gone swimmingly and all our prayers were  answered. Everyone looked beautiful, I saw tiny fingers in their first royal wave. Now, for the name . . . what do you think???? Be sure to leave a comment, and soon Vanna will choose the name of the lucky winner of the Royal Baby Gift! Did you hear that the royal mint will be giving a lucky 2013 silver coin to every British baby sharing a birthday with the new royal baby? The coin comes in either a pink or a blue pouch as a gift to new mommies and daddies. Just one of the cute things they do over there.♥

answered. Everyone looked beautiful, I saw tiny fingers in their first royal wave. Now, for the name . . . what do you think???? Be sure to leave a comment, and soon Vanna will choose the name of the lucky winner of the Royal Baby Gift! Did you hear that the royal mint will be giving a lucky 2013 silver coin to every British baby sharing a birthday with the new royal baby? The coin comes in either a pink or a blue pouch as a gift to new mommies and daddies. Just one of the cute things they do over there.♥

Talk about two people making one person! I hope Catherine has the baby soon so we know what we are celebrating (I’m sure she’s hoping the same thing!). Hope it’s a fat healthy pink baby that looks just like its Grandmama with all the grace of it’s great grammy. Such a happy time for our lovely Mother Country.

Talk about two people making one person! I hope Catherine has the baby soon so we know what we are celebrating (I’m sure she’s hoping the same thing!). Hope it’s a fat healthy pink baby that looks just like its Grandmama with all the grace of it’s great grammy. Such a happy time for our lovely Mother Country.

I’d love to show you before and after photos, but “before” would be SO bad, I could never show you ~ they looked like they’d come out of Miss Havisham’s house. You only get “after” pictures. (Love

I’d love to show you before and after photos, but “before” would be SO bad, I could never show you ~ they looked like they’d come out of Miss Havisham’s house. You only get “after” pictures. (Love

Must go finish washing the dishes for Twine! And make an Orange Lavender Polenta Cake from

Must go finish washing the dishes for Twine! And make an Orange Lavender Polenta Cake from